A few forthcoming books in Korean studies.

(The quotations are from publishers' introductory texts.)

Andrei N. Lankov: Crisis in North Korea: The Failure of De-Stalinization, 1956, U.of Hawaii Press (Link to publisher page) Andrei N. Lankov: Crisis in North Korea: The Failure of De-Stalinization, 1956, U.of Hawaii Press (Link to publisher page)

Dr Andrei Lankov's book was supposed to come out in August, but is now due later this year. The book is about the "last attempt" to curb Kim Il-sung's power by the reformist opposition in 1956; this important year in the Soviet sphere had percussions also in DPRK. Lankov traces the impact of Soviet reforms on North Korea, placing them in the context of contemporaneous political crises in Poland and Hungary. He documents the dissent among various social groups (intellectuals, students, party cadres) and their attempts to oust Kim in the unsuccessful "August plot" of 1956. His reconstruction of the Peng-Mikoyan visit of that year--the most dramatic Sino-Soviet intervention into Pyongyang politics--shows how it helped bring an end to purges of the opposition. The purges, however, resumed in less than a year as Kim skillfully began to distance himself from both Moscow and Beijing. The final chapters of this fascinating and revealing study deal with events of the late 1950s that eventually led to Kim's version of "national Stalinism." Lankov unearths data that, for the first time, allows us to estimate the scale and character of North Korea's Great Purge.

Kyung Moon Hwang: Beyond Birth. Social Status in the Emergence of Modern Korea. (January 2005; Publisher info) Kyung Moon Hwang: Beyond Birth. Social Status in the Emergence of Modern Korea. (January 2005; Publisher info)

If this is not coming out as a softcover it's unlikely that I'll order it, and the university libraries are busy paying rent to the governmental real estate corporation, so it may take time before I get my hands on this.The social structure of contemporary Korea contains strong echoes of the hierarchical principles and patterns governing stratification in the Choson dynasty (1392-1910): namely, birth and one's position in the bureaucracy. At the beginning of Korea's modern era, the bureaucracy continued to exert great influence, but developments undermined, instead of reinforced, aristocratic dominance. Furthermore, these changes elevated the secondary status groups of the Choson dynasty, those who had belonged to hereditary, endogamous tiers of government and society between the aristocracy and the commoners: specialists in foreign languages, law, medicine, and accounting; the clerks who ran local administrative districts; the children and descendants of concubines; the local elites of the northern provinces; and military officials. These groups had languished in subordinate positions in both the bureaucratic and social hierarchies for hundreds of years under an ethos and organization that, based predominantly on family lineage, consigned them to a permanent place below the Choson aristocracy.

As the author shows, the political disruptions of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, however, rewarded talent instead of birth. In turn, these groups' newfound standing as part of the governing elite allowed them to break into, and often dominate, the cultural, literary, and artistic spheres as well as politics, education, and business. This doesn't look like previously unknown history - the emergence of chungin (中人) specialist clerks and the previously discriminated illegitimate children of the yangban - but a detailed study is definitely welcome! (As if I was so sure there hadn't been one before...)

Alexis Dudden: Japan's Colonization of Korea: Discourse and Power (U of Hawaii Press, Oct 2004; publisher info). Alexis Dudden: Japan's Colonization of Korea: Discourse and Power (U of Hawaii Press, Oct 2004; publisher info).

As much as the famous Finnish linguist G.J. Ramstedt contributed to the knowledge of the Korean language with his research in the 1920s and 30s and with the publication of the Korean Grammar in 1939, his sympathies were with Japan in its East Asian policies; he went as far as to denounce some critical reports sent to the Finnish foreign ministry by the Finnish consule in China about Japanese activities in northern China in the 1930s. (Cannot quote from memory to which it referred in particular.) So here's a work that should help understand how the Japanese pursuits got the approval of a bourgeoisie (or right-wing) Finnish Asia scholar.From its creation in the early twentieth century, policymakers used the discourse of international law to legitimate Japan's empire. Although the Japanese state aggrandizers' reliance on this discourse did not create the imperial nation Japan would become, their fluent use of its terms inscribed Japan's claims as legal practice within Japan and abroad. Focusing on Japan's annexation of Korea in 1910, Alexis Dudden gives long-needed attention to the intellectual history of the empire and brings to light presumptions of the twentieth century's so-called international system by describing its most powerful--and most often overlooked--member's engagement with that system.

Pang Kie-chung and Michael D. Shin (eds.): Landlords, Peasants and Intellectuals in Modern Korea (Cornell East Asia Series, forthcoming; publisher info)This volume introduces, for the first time in English, the work of one of the major schools of historiography in South Korea. Centered at Yonsei University, the school focuses on intellectual and socio-economic history. A selection of studies illuminates the internal dynamics and historical roots of Korea’s transition to modernity and the division of the country and is a powerful refutation of the so-called "stagnation theory." The volume is in three parts: the first covers the period before the Japanese occupation; the second focuses on the socio-economic history during the occupation; and the last examines the work of three major intellectuals of the occupation period: Paek Nam’un, An Chaehong, and Yi Sunt’ak. "Powerful refutation of the so-called 'stagnation theory'; this theory refers to the view that the late Chosôn (Joseon) society and economy was somehow "stagnated" and didn't possess the qualities needed for (capitalist) economic development.

(But notice that denying the validity of the "internal development theory" or "sprouts theory" [maenga-ron] doesn't mean that one sees Chosôn as helplessly stagnant.)

I had an earlier note of a new book edited by the economic historian Lee Young-hoon; The Landlords volume should represent quite a different (if not opposite) view on this phase of Korean history; it should be noted that Lee's volume is not about stagnation but of downfall and crisis of the Korean economy in the 19th century.

Categories at del.icio.us/hunjang: books ∙ academic ∙ Koreanstudies ∙ contemp.history ∙ Koreanhistory ∙ socialcategories |

together, stays together". (<귀여워>는 극중 여주인공 (예지원)이 박수무당인 아버지(장선우), 그리고 배다른 삼형제들(김석훈, 박선우, 정재영)과 동시에 성적 관계를 맺는 역할로 설정돼 있음에도 불구하고 큰 저항감없이 각종 언론으로부터 주목받는 작품으로 소개되고 있다.)

together, stays together". (<귀여워>는 극중 여주인공 (예지원)이 박수무당인 아버지(장선우), 그리고 배다른 삼형제들(김석훈, 박선우, 정재영)과 동시에 성적 관계를 맺는 역할로 설정돼 있음에도 불구하고 큰 저항감없이 각종 언론으로부터 주목받는 작품으로 소개되고 있다.)

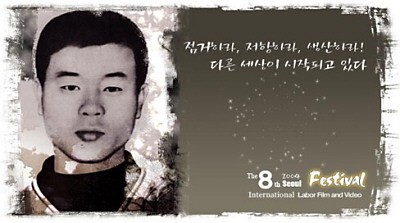

And who else is pictured in the festival homepage than the late Jun Tae-il (Chôn T'ae-il), who immolated himself in 1970 after a hopeless struggle to improve the working conditions in Seoul downtown factories and to have the labor laws observed. I think I'm repeating myself from some earlier post, but he is a figure that gives legitimacy to workers' concerns, as there's no way he could be painted red.

And who else is pictured in the festival homepage than the late Jun Tae-il (Chôn T'ae-il), who immolated himself in 1970 after a hopeless struggle to improve the working conditions in Seoul downtown factories and to have the labor laws observed. I think I'm repeating myself from some earlier post, but he is a figure that gives legitimacy to workers' concerns, as there's no way he could be painted red.

Andrei N. Lankov: Crisis in North Korea: The Failure of De-Stalinization, 1956, U.of Hawaii Press (

Andrei N. Lankov: Crisis in North Korea: The Failure of De-Stalinization, 1956, U.of Hawaii Press ( Kyung Moon Hwang: Beyond Birth. Social Status in the Emergence of Modern Korea. (January 2005;

Kyung Moon Hwang: Beyond Birth. Social Status in the Emergence of Modern Korea. (January 2005;  Alexis Dudden: Japan's Colonization of Korea: Discourse and Power (U of Hawaii Press, Oct 2004;

Alexis Dudden: Japan's Colonization of Korea: Discourse and Power (U of Hawaii Press, Oct 2004;